Morita therapy treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder

1. Understanding the disorder

Shoma Morita used the following example to illustrate the psychological mechanism of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Imagine someone suddenly struck by the idea that they might accidentally step on and kill their infant underfoot. Although it was a stray thought, the mental image of something too horrible to ever be allowed can make the mind recoil and strike fear into the heart. In a hypersensitive individual, that feeling could start a vicious cycle of sensation (fear) and attention to the sensation. In other words, fear of the stray thought, and then a focus on the fearful feeling, mutually stimulate and aggravate one another (seishin sogo sayo), until the original thought grows more powerful and prevalent.

The shinkeishitsu personality, with its perfectionist tendencies, will feel particularly strongly that such a frightening thought is unacceptable, and will try to banish it from consciousness. However, resisting the thought leads to stronger fixation on it. The contradiction between someone’s ideas – in this case, of what they should be thinking – and reality – here, what they actually are thinking – is the mechanism by which thoughts become obsessions. (The Morita term for the mechanism is shiso no mujun.)

Obsessive thoughts, in turn, bring further anxiety and distress. Repeated attempts to eliminate these unpleasant emotions then become compulsive acts. Typical examples include people consumed with worry that they might be unclean or contaminated, who then repeatedly wash their hands, and individuals who engage in repeated checking behaviors throughout the day because they are fixated on the fear they have not done something correctly or completely. In the course of performing these rituals, sufferers grow increasingly anxious that their performance is imperfect: “Did I really get myself clean?” “Have I really confirmed that everything is in order?” This may cause them to go through the entire ritual again, thus initiating a vicious cycle of increasingly disproportionate, senseless behavior.

2. Inpatient therapy

The following review of Morita therapy inpatient care for obsessive-compulsive disorder centers on diary guidance, in which patients keep and submit diaries for therapist feedback.

Note that in the interest of protecting patient privacy and anonymity, some of the information presented in these case studies has been slightly altered.

■Patient: Mr. A, a 21 year-old male

The primary symptom in this case is an irresistible urge to wash hands and engage in the cleansing ritual of sprinkling salt whenever the patient catches sight of a person dressed in mourning, or upon hearing any word related to death.

Mr. A has an anxiety-prone personality. He began living alone for the first time after entering university. During a period beginning two years before his initial assessment, a number of his friends died in events that occurred in succession. From that time, he has been unable to avoid washing his hands or sprinkling salt in a cleansing ritual any time he sees a person dressed in mourning, or whenever he hears spoken language that has any relation to death. Symptoms gradually worsened to the point that he would sprinkle salt throughout his own room in a Shinto-style purification ritual, and it became difficult for Mr. A to leave his residence alone. Therefore, he returned to the family home in his hometown, but there he began requesting that family members also participate in the salt purification ritual. In addition, he refused to eat with anyone in his family other than his mother, in an attempt to avoid conversation on any topic that might be associated with death. On recommendation by the consulting psychiatrist, Mr. A came to the clinic for voluntary admission. He reports that the salt-sprinkling ritual has continued to the time of admission.

≪Course of treatment≫

In the following passages, portions in the corner brackets「 」are excerpted from Mr. A’s diary, while the material in parentheses ( ) has been selected from the treating therapist’s comments.

Out of bed (end of the rest and isolation phase) – First week

「I was observing the other patients at their work today, but I just followed like a puppy dog, on the verge of tears the whole time. I still don’t fit in, I don’t feel comfortable here.」

(Working hard to stick with the observation assignment even though you were fighting back tears shows that you have the desire to improve.)

Out of bed – Second week

「I went to the supermarket to pick up some detergent, but I became worried about possibly seeing somebody in mourning, so I tried not to look or see anything around me.」

(Were you able to buy the detergent? The most important thing is whether or not you accomplish your objectives.)

「「I have been assigned to take care of the animals, but I hate to think of everything that lies ahead with that. There’s so much to do, I just want to run away from it all.」

(And yet, for all the grumbling, you seem to take on the work in earnest. Don’t you agree?)

Mr. A continued complaining this way during this phase of therapy, but he successfully helped train birds that the clinic raises for homing pigeon races (by taking them from the facility to remote locations and releasing them to return to their nests). In the course doing this work, Mr. A was able to expand his range of off-clinic activity.

Out of bed – Fifth week

「One of the tropical fish in my care died, so I have been in a gloomy haze, but since the work is my responsibility, project planning is a stronger focus than sadness right now.」

(The heart is volatile, you’re bound have these sorts of emotional ups and downs. Now is the time to commit to doing what is in front of you.)

Out of bed – Sixth week

「(After being seized with debilitating fear when another patient brought an injured crow to the care facility) I’m at a loss about whether I should continue treatment, or if it would be better to get discharged. I’m just sleeping all day – it’s really hard to feel good about that.」

(Train yourself to take action and carry out your tasks without being controlled by moods. That will be key to your psychological growth.)

(From the next day’s diary) 「I don’t know what to do with myself, but I do know that I don’t feel like running away.」

Mr. A finally decided to ride out the fear that was gripping him and stay on with the therapy. From that point on, he continued doing his work, even as his anxiety persisted.

Out of bed – Tenth week

「I was able to visit my university by myself and return, without sprinkling salt anywhere.」

(Good job stepping up and accomplishing your objective.)

In consultation with the therapy team, Mr. A established a post-release plan, and was discharged, completing a three-months course of group living treatment. He then returned to his university and was able to graduate without incident the following year. No relapse of symptoms has been observed at any time subsequently.

3. Main points in the therapy

Engaging patients in concrete action-taking is the major aim of Morita therapy treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Specifically, therapists emphasize the following key points.

1. Let anxiety be, without engaging in compulsive acts in an attempt to relieve it. At least, try to pause to lengthen the response interval before acting on the compulsion.

Therapists advise patients that stopping compulsions overnight may be an unrealistically difficult goal, but they can extend the interval between the anxiety stimulus and the compulsive response acting less reflexively.

2. Quickly shift to constructive activity. Interrupt compulsive behavior for a measured period of time.

To break the pattern of maintaining compulsive rituals until negative moods subside, patients are encouraged to leave the triggering distress alone and move on to the next constructive action. Setting a time-period goal for continuing this positive activity, such as five minutes, is one method of interrupting compulsive behavior.

3. Find a happy medium without lapsing into all-or-nothing thinking. Any action is better than no action at all.

Many patients are perfectionists, a compulsive trait in itself. They tend to settle into all-or-nothing patterns of action or inaction – if they can’t accomplish everything, they won’t engage at all. Perfectionists have difficulty starting anything, since they seek a perfect result, and therefore interpret nearly all real-world outcomes as unfavorable and not worthy of pursuit. This, in turn, tends to limit the scope of activity they are willing to try. It is important to encourage these patients to shed their self-limiting inhibitions, and do something rather than nothing. The goals are to accept that acting even 30 or 40 percent of the time is success, and to attend to what needs to be done in the present moment, without overthinking it.

4.Develop a flexible state of mind

Some inpatients are such captives of “how it should be” thinking that when they are assigned to water the plants on the facility grounds, they will actually continue watering in the rain. Therapists need to remind these patients to be flexible enough to assess situations and act accordingly.

5. Develop a purpose-oriented perspective, where the criterion for success is not whether or not symptoms are present, but whether or not goals are achieved

In a shopping scenario, for example, patients tend to pay attention to whether or not they experience symptoms in the store, but in Morita therapy, success is measured by whether the person actually manages to purchase the items they need, irrespective of the presence or absence of symptoms. Thus, therapists advise patients to judge outcomes on the standard of achieving the goal involved.

Morita therapy for social phobia

1. Understanding the disorder

Shoma Morita wrote extensively on the fear of interpersonal relations (taijin kyofusho) and related disorders (social phobia and social anxiety) that are characterized by symptoms such as fear of blushing. He observed that sufferers “feel shy or embarrassed, feel ashamed of themselves for feeling shy or embarrassed, and try not to feel embarrassment.” In short, people with this phobic mindset are embarrassed about embarrassment, or, as Morita himself observed, the essence of social disorders is fear of shyness. He described this as a double-edged phenomenon: on one side of the coin is the desire to be admired by others, and on the other is the fear and anxiety of being rejected. In shyness, then, the fear of being shameful coexists with the desire to be recognized as excellent. This duality of fear and desire is simply a fact of the human psyche. However, people with social phobia interpret the emotional and physiological responses that arise from that reality, like embarrassment and blushing, as wrong and unacceptable. They go to elaborate lengths to deny or eliminate the symptoms of shyness even as they are experiencing them, but the fixation on symptoms only increases their prevalence, and intensifies the embarrassment, in a vicious cycle of shame.

2.Outpatient therapy

The previous section addressed the proper treatment of patients whose social phobia makes school, work and other elements of life in society difficult. In such severe cases, inpatient care may be recommended, since it provides an opportunity to participate in group living and develop the capacity for constructive action. However, patients with relatively milder cases may be best served by outpatient treatment. The following case study is an example of Morita therapy outpatient care.

■Patient: Ms. B, a 34 year-old female

The patient’s primary complaint was a feeling that her facial expression stiffens when speaking to another person, who can then recognize her tension and anxiety. For that reason, eye contact causes her distress.

≪Course of treatment≫

The planned therapy regimen was limited to six months. Therapy consisted of one approximately 30-minute session every two weeks, as a rule, in a 12-visit course, conducted in combination with diary guidance. In consensus with the patient’s wishes, no medications were administered during the course of treatment.

(Initial interview session)

Ms. B entered university after age 30. Before any class in which she is scheduled to make a presentation, she begins to feel tense, growing increasingly nervous as the presentation draws nearer. When she actually delivers the talk, she feels her face stiffen, and perceives scorn and contempt from her classmates observing this facial expression. At the same time, however, she believes that when the audience tries not to look at her tense face, that is a sign they are aware of her nervousness. When her doctor asked her to relate her feelings in these situations, she described herself as scared, embarrassed and pathetic. Next, she was asked what she thinks her emotions are asking of her. In other words, the therapist was trying to find out what desires she is holding on the other side of the fear, which the fear is trying to draw her attention to. She spoke of her wish to be more accomplished than other people, to be recognized, to be well thought of. Ms. B also wistfully wondered how other people could so be so calmly self-assured, when she thinks about her facial expression hundreds of times a day.

Her treating therapist explained the fact that both the feelings and the desires Ms. B harbors are natural, and that anybody facing the same circumstance would also be nervous and anxious to some extent. In addition, the doctor elucidated her vicious cycle of sensation and fixation, suggesting that when she finds herself in a tense situation, she fights not to be nervous, and concentrates on the battle, but this fixation only intensifies the nervousness.

(Second to fifth interview sessions)

In her interviews as well as her diary entries, Ms. B repeatedly relates experiencing nervous anxiety in any number of situations. Referring to her interaction with classmates, she stated “I can’t even say hello without being awkward. It’s just pathetic. I’m so disgusted with myself.” Her therapist pointed out that this level of self-criticism arises from the “should-be” mindset, a rigid belief in how a person and their world are supposed to operate. This attitude also drives her to try and control her emotions and facial expressions to meet some unreasonable expectation. The therapist directed her to adopt a new standard for self-evaluation. Rather than judging her behavior based on the presence or absence of symptoms, it would better serve her to assess whether or not her action accomplishes the goal she is trying to attain with it. (In other words, Ms. B was advised to adopt a purpose-oriented attitude.) The final piece of advice was to pay more attention to what the other party is saying in the next conversation, even as she experiences nervousness within herself. In other words, focus on the conversation partner (instead of her internal conversation) and try to become a better listener.

Ms. B subsequently reported acting on the advice and experiencing less nervousness than she thought she would, although she admitted that it is still quite hard for her to be attentive enough to be considered a good listener. Asked at this point what she would do if her symptoms were to improve, Ms. B related her desire to continue her studies, and to eventually open a language school. She also wishes to expand her circle of friends. Her therapist explained that Ms. B can move closer to realizing those desires, if the desires actually lead her to action. Moreover, this sort of constructive action is feasible right now – she need not wait until the nervousness is gone to take action. The therapist suggested that Ms. B start to widen her range of activity, even as she continues to experience nervous symptoms.

(Sixth to eleventh interview sessions)

At this juncture of therapy, Ms. B was less often trying to avoid situations that she anticipates will cause her nervous distress. One of her diary entries paints a picture of Ms. B headed to a necessary but fraught engagement, even though she was “on pins and needles.” On the one hand, the therapy team observes evidence that Ms. B is moving toward a more action-oriented attitude – continuing with her studies, spending time with friends and so on. However, one can also see glimpses of symptom-driven behavior, such as her continued inability to greet people unless they go first, or an episode where Ms. B never reached her destination because she couldn’t bring herself to ask street directions.

From the sixth interview forward, in consultation with her therapist, Ms. B planned direct action assignments to execute and then report in the following session. One of these, asking a passerby for directions to the store, resulted in her arriving there just in time before closing. She also took on the task of greeting people in her neighborhood, and found that at least a few were friendly and easygoing in response. The therapist reminded Ms. B of the fact that none of the unpleasantness that she had anticipated actually befell her when she took the initiative in saying hello. The doctor also noted that Ms. B recognizes that her discomfort was eased by the warm greetings her neighbors returned. Her therapist urged her to continue and redouble her efforts to take purpose-oriented action.

However, Ms. B stated that she has been unable to take action on another of her worries – looking her conversation partner in the eye. Here, the therapist got the impression that Ms. B is fixated on the task and its attendant emotions, and so offered that making eye contact isn’t the only or the paramount issue in communication. Rather, clearly answering one’s interlocutor is the important point, even if we may not be looking the other person directly in the eye. Ms. B also mentioned frequently focusing on her own nervous distress whenever she makes efforts to tune into what her conversation partner is saying. The treating doctor was similarly reassuring about this, advising Ms. B that it will be fine to simply return her focus to other person’s talk whenever she notices that she has drifted.

(Final interview session)

By this time, Ms. B had taken up cooking and decided to attend a cooking school. This would seem to indicate that Ms. B has broadened her interests and hobbies, and has gradually developed an attitude of taking action to realize newfound passions.

In this, the final of the 12 scheduled sessions, Ms. B reviewed her progress over the course of treatment. She offered that she now believes she can achieve her dreams for the future, as long as she continues taking action toward them, even as she continues experiencing some nervousness. Ms. B also observed that she has become more capable of focusing on and carefully listening to the person before her in conversation. On the downside, she indicated a continued tendency to brood over things she has said and done after the fact, using the perfectionist “should say this, should do that, should be this other way” yardstick, measuring herself against the commandment to always “stand proud and confident.”

In summary, Ms. B has shown improvement, albeit modest, over the course of treatment. With the offer of the option to return in three months for additional sessions if she wishes, the therapy team concluded the current course of treatment.

Morita therapy treatment for panic disorder

1.Understanding the disorder

Shoma Morita himself suffered panic attacks when he was a young man. His own experience in overcoming anxiety disorder is widely considered to be the seed for what eventually developed into Morita therapy. Morita observed that panic attacks have a mechanism of symptom formation which he termed the “vicious cycle of sensation and attention.” One example would be a person who, after witnessing a heart disease sufferer actually perish from the disease, begins to harbor worries of meeting the same fate. Some time thereafter, the person feels mild heart palpitations, which are natural and unrelated to any cardiac condition. However, the individual links the sensation of an irregular heartbeat to the experience of witnessing the death, which then engenders a fear of dying. Naturally, the fear sets off further palpitations. This causes the person to pay increasing attention to their heart, and as they do, their anxiety worsens. Attention and anxiety mutually influence and amplify one another until the heart palpitations finally become severe.

In Morita therapy terms, this vicious cycle of mutually escalating interaction between attention and sensation is known as seishin kogo sayo, or psychic interaction. It is one of the causative mechanisms of toraware (entrapment by fixation). The phenomenon means exacerbating anxiety by trying control it.

2.Outpatient therapy

In his original practice, Morita instructed his clients to intentionally trigger panic attacks so that they could chronicle the details in an observation diary. Today’s treatment method generally emphasizes a greater degree of process, and often incorporates medication in a combination therapy. The following case study exemplifies the current Morita therapy approach in a psychiatric department’s outpatient practice.

■Mr. C, a 32 year-old male

Mr. C stated that in the period beginning two months before his initial visit, he began having problems at work, which he then had to deal with on a daily basis. He was drinking heavily to cope with the stress. One evening he experienced palpitations during sleep. He awoke with chest pains, shortness of breath and numbness in his limbs, accompanied by intense fear “that this might be the end. I thought I might die right there and then.” He called an ambulance and was examined at the hospital, but EKG and other testing showed no detectable abnormality. Three weeks later, a similar night attack occurred, and Mr. C was once again examined in the emergency room. On this occasion, he was given a prescription for anti-anxiety medication at bedtime, which he continued to take for a time. However, two weeks prior to his initial assessment at this facility, he suffered a third attack, this time while taking a bath. Again he was transported by ambulance to the hospital, where he underwent more extensive testing, but the doctors still did not detect any medical abnormality. In the interim, he has been experiencing anxiety over the possibility of another episode, such that he cannot be alone and has returned to his family home. He has also been avoiding riding in trains and getting in the bath. On the referral of his primary care physician, Mr. C has undergone a psychiatric evaluation.

≪Course of treatment≫

Initial visit

The treating psychiatrist explained that panic attacks “activate the autonomous nervous system, which rapidly escalates tension as part of a wider physiological response. However, this will naturally subside if it is left alone.” The doctor gave instructions on breathing techniques that can be used when hyperventilation occurs in conjunction with a panic attack. In addition, Mr. C was advised to limit alcohol consumption, since excessive drinking may be the proximate cause of an attack. Mr. C indicated a preference to avoid medication, because “so far I have tried to stay off drugs as much as possible.” However, the therapist assured Mr. C that “the medications are only there to support as you work on a plan to restore your life,” and prescribed an anti-anxiety medication and an SSRI class antidepressant.

After two weeks of treatment

Although no major panic attacks have occurred since beginning therapy, Mr. C has experienced a pounding heartbeat and difficulty breathing during meals and when taking a bath. Both of these symptoms have been mild, but he still suffers from anticipatory anxiety that another attack may be imminent, and so continues to refrain from bathing in the tub. His therapist explained the mechanism of anticipatory anxiety, and encouraged Mr. C to muster the courage to take on the activities that he has been avoiding.

After four weeks of treatment

Mr. C’s mood has stabilized substantially over the last two weeks. He resumed his independent single living several days ago.

After two months of treatment

Mr. C was taking anti-anxiety medication every other day at the outset of therapy, but the treating psychiatrist determined that in the absence of any serious issue, the prescription for regular use could be discontinued. After a short period off the medication, Mr. C reported one episode in which he experienced sudden feelings of anxiety during a visit to the barber, but he managed to endure and withstand the anxious distress without incident.

After four months of treatment

Mr. C reported experiencing heart palpitations following a bout of heavy drinking, which he addressed by taking anti-anxiety medication that had been prescribed for use as needed. The therapist offered praise for Mr. C handling the situation launching into panic. However, the doctor also noted that a pattern of drinking heavily with increasing frequency, leading to chronic sleep insufficiency, represents a turn back toward the life that triggered the symptoms in the first place. Therefore, Mr. C was urged to pay more attention to the lifestyle aspect of his condition.

His subsequent efforts to keep regular hours and lead a more orderly life showed good progress, and the therapy team discontinued the other prescription, for the anti-depressant, within a few months. Mr. C continued without any recurrence or episode of note, and the therapy team concluded treatment.

3. Key features of Morita therapy treatment

The six concepts outlined below are fundamental to treating panic disorder in the Morita therapy approach.

(1) Educate the patient about panic disorder.

At the outset of treatment, therapists explain that panic attack symptoms are indicative of a natural physiological stress response. In medical terms, this is a rapid shift in the autonomic system balance to the sympathetic nerve state, but it is more commonly known as the “fight or flight” response. Since this response is a common and naturally occurring phenomenon, the events that most patients fear during a panic attack – such as passing out or losing control of themselves are never going to happen – much less are they going to go into cardiac arrest or even die, as many worry they might. Therapists can be confident in informing patients of these facts. Moreover, panic attacks resolve naturally, and a person who has one will usually return to normal within a few minutes to an hour without taking any action at all. In our own practice, we often liken a panic attack to a sudden, brief downpour of rain.

(2) Employ effective communication that supports patient understanding and adherence to prescribed medication.

a) Encourage patients to think of medication as adjunctive therapy that supports the ultimate objective of rebuilding their own lives.

Simply prescribing medication without involving the patient in the treatment plan may make them believe that they are helpless without drugs. To overcome this feeling of powerlessness, clinicians explain that healing power is internal. Recovery is driven by the patient’s own initiative and effort, while the medicines merely play a role in helping the process along.

b) Remind patients that medication serves to lessen the severity and frequency of panic attacks and reduce anxiety.

When patients, and sometimes physicians, aim for the complete elimination of anxiety though drug therapy, they run the risk of unnecessary medication changes and “dose creep” – continuous, unlimited increases in the dose of medication being administered. As they discuss the efficacy and expected outcome of drug therapy, therapists can check unrealistic patient expectations by framing the objective in terms of reducing anxiety to a tolerable level.

c) Inform patients of expected and common side effects.

Patients tend to have fears about adverse drug reactions. It is important to ease their concerns by explaining the expected and common side effects that might realistically occur, and separating those out from anxieties that are not based on the actual risk involved.

d) Assure patients that they can always discuss concerns about their medications during interview sessions.

Talking with patients about their medications can heighten their sense of security about the drugs. Beyond that, the discussion also invites them to recognize a pattern of over-caution in their everyday behavior. Do they look before they leap, confirm everything is safe… and then not take the plunge anyway?

(3) Elucidate the vicious cycle that acts to aggravate symptoms.

Most patients who describe constant worry that a panic attack is eminent will buy into a hypothesis that may seem paradoxical: the more they struggle to deny their anxiety, the less control they have over it, and the more they wind up aggravating it. Panic disorder commonly develops from the anticipatory anxiety that leads individuals to avoid situations they fear will trigger an attack. That, in turn, narrows the range of activity they are willing to pursue in daily life. Therapists need to fully explain the mechanism of anticipatory anxiety, clearly delineating the difference between symptoms of the anxiety and actual morbid (disease) symptoms.

(4) Illustrate how anxiety factors into the adage “living in fear of debilitating disease is itself disabling.”

Anxiety can drive patients to constantly monitor their physical condition, looking for any sign that an attack may be coming. When they start to feel the faintest symptoms of panic, they may get off the train before their destination, or drop what they’re doing to rush to the hospital. In some cases, they may try to avoid going out alone. This is what Morita therapy calls hakarai, the attempt to control, fight or avoid anxiety. It only exacerbates the suffering and impinges on a person’s lifestyle, to the point that in extreme cases, even setting foot outside the house becomes a daunting challenge. Patients in this self-defeating vicious cycle invite outcomes that run counter to their true desire to live a better, healthier life.

Therapists invite each patient to consider how this pattern fits the life they are leading. When they look realistically at their way of living and coping, patients may recognize themselves in the adage “living in fear of debilitating disease is itself disabling.” That realization leads patients to the next level of understanding and recovery.

(5) Encourage patients to leave anxiety as it is and aim for restoring a productive lifestyle.

The patients’ work at this stage consists of doing whatever they can do toward rebuilding their lives, taking action while leaving anxiety as it is. Naturally, that may include taking on activities that anticipatory anxiety had previously prompted them to avoid, such as leaving the house and getting on public transport. However, patients need not prioritize direct challenges in order to make progress. Treating therapists encourage their patients to use their time effectively, with an orientation toward constructive action, even if they are just spending it at home. They guide their patients toward engaging in more varied activity, to realize their desire to live life to its full potential.

(6) Suggest that patients reconsider their previous (pre-symptomatic) approach to life.

Panic disorder patients often have perfectionist attitudes about how things are “supposed to be.” This outlook leads them to try and meet self-imposed, unreasonable performance ideals at work and in society generally. It opens the door to physical and mental stress, as well as overwork. A key theme for patients at the conclusion of therapy is reconsidering and modifying the “should-be” style of thought and living that presaged their symptoms.

Morita therapy treatment and life guidance (yojo) for depression

1. Understanding the disorder

Approximately 70% of patients with depression respond quickly to antidepressant treatment and rest. However, as the number of patients diagnosed with depression grows, the 30% who do not improve, or show partial response, even with an extended course of standard therapy have become a highly visible issue in psychotherapy. One of many factors at play in depression becoming chronic is the attitude toward mental health seen in personalities disposed toward the disorder. Individuals with depressive personality tendencies share traits such as conscientiousness and devotion to work. However, one subset of that population stands out for its absolutist expression of these driven qualities, the so-called “should-be” mindset. Patients who have symptoms that they believe they ought not have may grow impatient with the recovery process, or try to push things beyond what is reasonable during treatment. This, in turn, is a causative factor in the depression becoming chronic.

Morita therapy encourages patients to reorient their attitude in respect to mental health, more toward accommodating the natural healing process. Guidance from this perspective reflects the traditional Japanese medical philosophy known as yojo, or “cultivating life.”

Psychiatrist Hisao Nakao describes yojo as a method to potentiate natural healing capacity. “Diseases that can be cured by the body’s own healing power are treated by optimizing the natural healing response to the contours of the particular disease. Physicians seek to eliminate adverse factors that interfere with the process, while preventing both the disease and the healing process itself from setting off events that would aggravate the condition.” Recovery from depression essentially follows the same natural healing pathway for disease that Dr. Nakao outlined. Shoma Morita similarly stated that fostering patients’ natural healing ability is the foundation of therapy. “Disease should generally be treated by activating, supporting and promoting the vital force (natural healing power) within.” Thus, therapy from the yojo perspective is a wellness restoration model. To that end, patients are encouraged to find the path to mental health in the context of their own everyday actions and attitudes. Therapists ask their patients to think of lifestyle as a cure. “What outlook on life would be the most desirable and expedient for you to break free of the depression?”

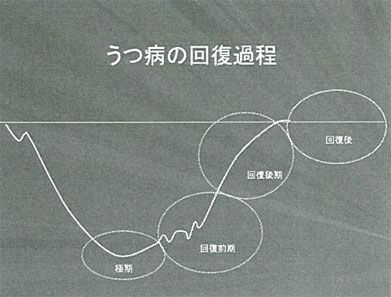

From this holistic perspective, we have proposed a wellness-centered yojo treatment for depression that employs the key Morita tenet of accepting things as they are (agugamama). As it applies in this case, arugamama means patients accepting the fact that they suffer from the disorder. When they operate from that realistic perspective, they can make appropriate lifestyle modifications to avoid the vicious cycle of symptom aggravation during recovery. Patients are encouraged to gradually move from rest to healthy physical and mental activity in the recovery period, toward realizing their desire for a full and meaningful life. Constructive activity, in turn, can further the natural healing process, creating the opportunity to generate a virtuous cycle of action and wellness.

The following section introduces some of the yojo living-guidance instructions employed in therapy for each phase of depression.

≪Yojo guidance in the acute treatment phase (peak symptoms)≫

(1)At this stage of treatment, any action designed to improve the condition is unlikely to work. When symptoms are at their peak, getting some rest is the top priority, so preparing a tranquil environment is the most important thing.(All good things come to those who wait.)

(2)It is essential that patients continue to visit the clinic throughout the depression recovery process, and adhere to their prescriptions. Yojo is a natural healing process, but that doesn’t mean trying to recover solely on one’s own power without “relying on drugs.” The notion that people need to pull themselves up by the bootstraps to overcome depression is an example of dogmatic “how it should be” thinking that can prompt patients to push themselves too far, too fast.(Outpatient visits and taking medication as prescribed are indispensable elements of treatment.)

≪Yojo guidance in the early recovery phase≫

(3)Yojo therapy is designed to help ease depression over time, by balancing work and rest as the symptoms require, rather than rushing into a fight with them. However, for the strategy to succeed, patients need a yardstick by which to measure the severity of their symptoms at any given time, since subjective judgment is difficult and symptoms may be subtle. Clinicians suggest using fatigue, a signature depression symptom, as an indicator. When clients report feeling more fatigued, rest is the predominant treatment mode, whereas when the fatigue is less pronounced, patients can be encouraged to try taking action, starting with relatively easy tasks on hand.(Flexible response)

(4)Early in recovery, patients’ healthy energy (i.e., their desire for life) is being activated. However, the positive energy remains faint at this point in the process. Therefore, it’s important to advise patients to let the “green shoots” of healthy desire grow naturally, rather than strangling them with unrealistic “should-be” expectations of fast or perfect results. For example, if the patient feels a budding desire to step out for some fresh air, they are welcome to go outside for a leisurely stroll. If they then feel like walking a little longer, they can surrender to the feeling and stretch their legs a bit more. In this way, the direct experience of light activity in the early recovery phase provides the impetus for further action.(When patients feel like doing something, they can take action on it.)

≪Yojo guidance in the later recovery phase≫

Guidance for patients who have demonstrated 60%-70% recovery relative to their initial state

(5)Patients who have recovered to this point will benefit from developing a regular lifestyle with a well-planned daily routine. They should wake up, take meals, and go to bed at roughly the same time every day. Within this healthy schedule, they can also gradually increase their engagement in constructive work.(Create a regular life pattern.)

(6)Since depression patients tend to spend their days in rumination about the past and/or worry over the future, it is increasingly important for them to become mindful of the present as treatment progresses. The shift in orientation entails proceeding to action, doing what needs to be done. Patients are encouraged to take on the task before them, complete it, then focus on the next task. The idea is to develop the habit of doing work that makes each day fulfilling (to the extent the patient’s degree of recovery allows). Setting modest goals and then working to attain them is a good strategy in this phase.(Create a regular life pattern.)

(7)As therapy begins drawing to a close and patients contemplate returning to life in their communities, they often harbor growing insecurity over what might come next. However, this sense of apprehension is different in nature from the anxious impatience that characterizes initial-stage depression. In this case, concern about the outcome is the reverse side of the healthy desire for things to work out. “I hope I can go back to work without any hitches” is a modestly anxious sentiment, but one that might naturally be expected in the situation. Therefore, there is no need to bend over backwards trying to eliminate this sort of anxiety. Better to leave it alone, and think of the situation as one would a threatening sky. It may rain, but the storm will pass. When they actually resume their life, most people find that their anxiety about it naturally dissipates day by day.(Every storm runs out of rain.)

(8)”When I return to work, I’m going to have to make up for all the trouble my absence caused my coworkers.” Many people seem to feel this way, but the need to impose compensation on one’s self to try and square one’s perceived imposition on others is an example of a rigid and unhealthy “how things should be” outlook. People who have recovered their mental health believe in how things are. Their orientation is forward-looking, in this case, toward engineering a soft landing. They focus on concrete measures to ease their way back, such as reduced-load work arrangements.(Don’t get caught up in how things should be, get real about how things will be.)

≪Guidance for post-recovery maintenance and preventing relapses≫

(9)Recovery can be a catalyst for reflection on one’s lifestyle before the depression was triggered, and a chance to alter it to a healthier way of being. A commitment to avoid overwork, take time out for one’s self, and adopt a more reasonable approach to life can be the cornerstone of better health moving forward. Viewed in this light, the experience with depression represents a step toward further maturity.(A consolation in being sick is recovering to a better state than before. Bad luck can bring good luck.)

(10)Rather than struggling to deny the fear of depression in the name of preventing a relapse, it is better to dare let it linger in the back of one’s mind. Remembering what the episode’s initial symptoms felt like can be particularly helpful, in case it happens again. It allows a patient to be proactive as soon as they recognize symptoms coming on, by first resting for two or three days, then moving the next scheduled appointment up to get it checked early.(When we endure something unpleasant, we forget about it once the immediate pain is past.)

Yojo life guidance-based therapy as described in this section is generally practiced in outpatient settings. However, it bears mentioning that patients who do not achieve satisfactory results have a further card to play: entering Morita therapy inpatient care to jump-start the recovery process.

Professor Kei Nakamura, The Jikei University School of Medicine